The idea of exploratory mountaineering can conjure up visions of the Fedchenkos walking up the Jiptik valley and sketching out the locations of the peaks surrounding the Jiptik / Schurovsky glacier, or Shipton and Tilman setting up their plane table in the Nanda Devi sanctuary to survey the remotest corners of British India. But what does exploration entail when the whole world is at your fingertips on google earth? Well, the good news (for those who want to explore) is that google earth only gives you a quite limited set of information. It can give you only the vaguest hint of whether a remote mountain valley is accessible or not – I should know, after my 2014 trip to Kyrgyzstan! The resolution of the surveying is poor compared to the maps we are used to in Europe from the British Ordnance Survey (OS) or the French Institut Geographique National (IGN), for instance. And information on the terrain is lacking, it is hard to say if a slope is a pleasant grassy ramble or a terrifying scrabble of dangerous unstable choss. You cannot see how easy it will be to cross a river, or whether there are seracs, etc, etc.

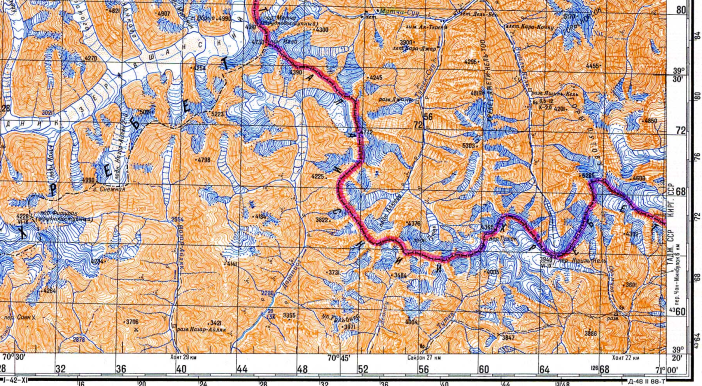

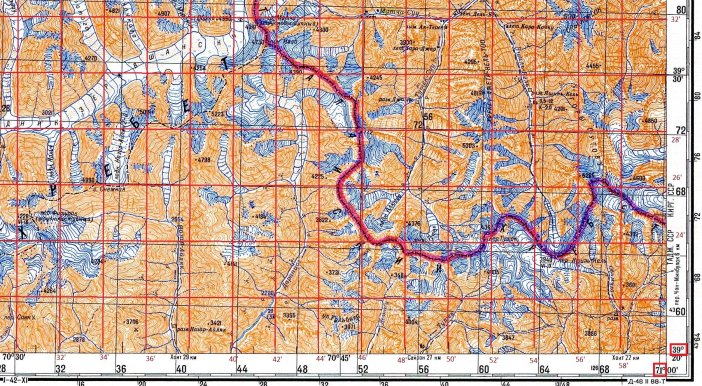

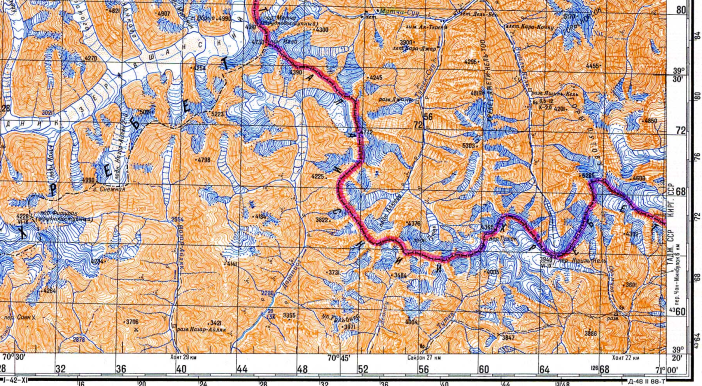

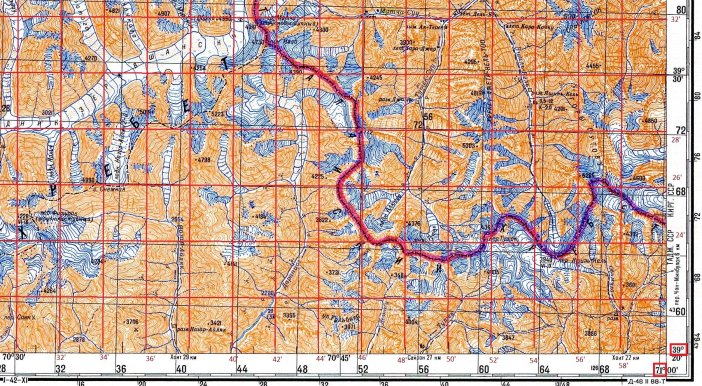

In the former Soviet Union however, there are better maps available than google maps / earth. The entire USSR was mapped to a high standard during the Soviet era, and at least a large proportion of these maps are now available to download for free from maps.vlasenko.net. As a subjective opinion, I would say that the surveying on these maps is as good as that on the OS or IGN maps, and the Soviet maps have a certain beauty about them:

But there are shortcomings; generally they are only available in 1:100,000 resolution – understandable when you consider the size of the country the Soviets had to map! So the features on display on the maps are quite limited compared to what we are used to on OS or IGN maps and information on the kind of terrain underfoot is sometimes also limited. The youngest of the Soviet maps were done in circa 1985 and the glaciers have receded a lot since then. And there is also another problem – the Soviet maps use a datum (Pulkovo 1942 Krasovskii spheroid) which absolutely no-one uses anymore. Try finding a GPS with that one on!

So a few years ago I developed a method for drawing onto the electronic copy of the Soviet map a WGS84 datum; this is the datum used by google earth and available on any GPS. The method involved selecting 3 prominent summits or other land marks, obtaining the co-ordinates of their pixels on the electronic copy of the Soviet map and then using google earth to obtain the WGS84 datum longitude and latitude. Using this information you can then calculate where to put the WGS84 longitude and latitude grid lines (i.e. the datum) on the map – even accounting for the fact that the grid lines do not run parallel to the x and y axes.

So you can now turn on your GPS, read off your location and place yourself on the map. So when your driver tells you that you have arrived at the point he agreed to drop you off you can inform him that there is another 10 miles still to go, when you are jungle-bashing your way up some remote valley you can see what a depressingly short distance you have advanced in the past 4 hours, etc. etc. You can see the reasons why doing this is worth the effort!

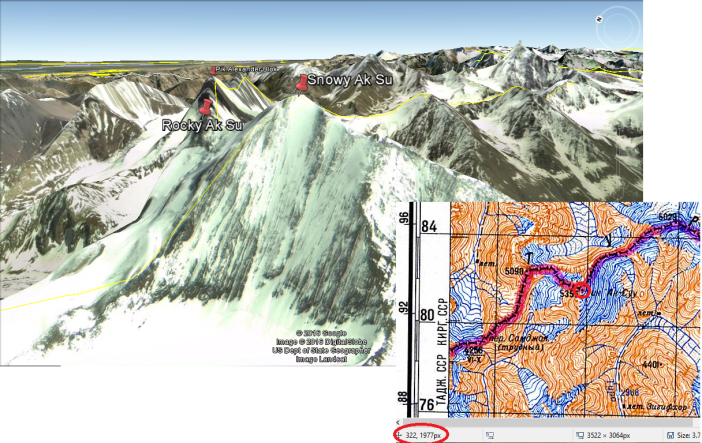

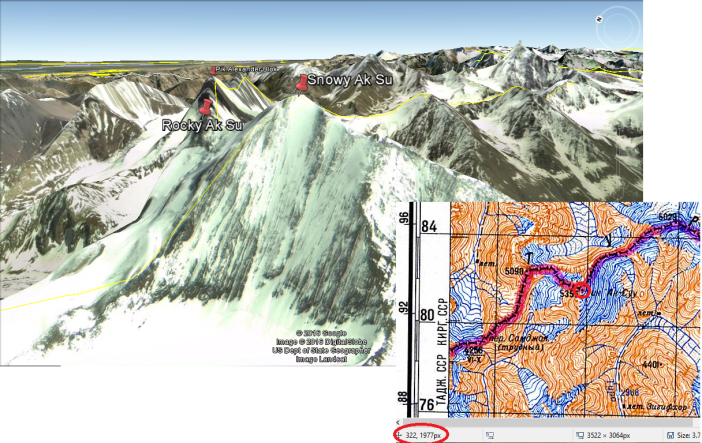

My previous method, however, had the shortcoming that, whilst you can use the co-ordinates of some additional summits or landmarks to check that your grid lines are not too wide of the mark, you can only directly use 3 data points in calculating where they should be. And in each data point there must be some error – google earth often chops the tops off summits and consequently can get them in the wrong location, stream and road junctions can move a bit, etc. Here is an example of a data point:

The summit of Ak Su is on the same Soviet map as the Jiptik valley so was used as one of the data points for the calibration. Snowy Ak Su is the higher and more pronounced summit, which has a placemark on the Soviet map. You read off the pixels from the map, and the WGS84 latitude and longitude from the google earth placemark.

So this spring I developed a more accurate method which allows you to use as many data points as you have the patience to enter, and use regression analysis to work out the locations for the grid lines which will produce the smallest error in the conversion between pixels and WGS84 co-ordinates for all the data points you have entered.

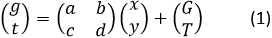

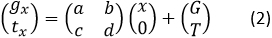

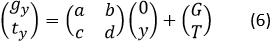

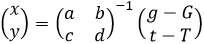

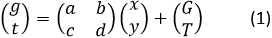

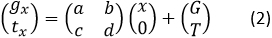

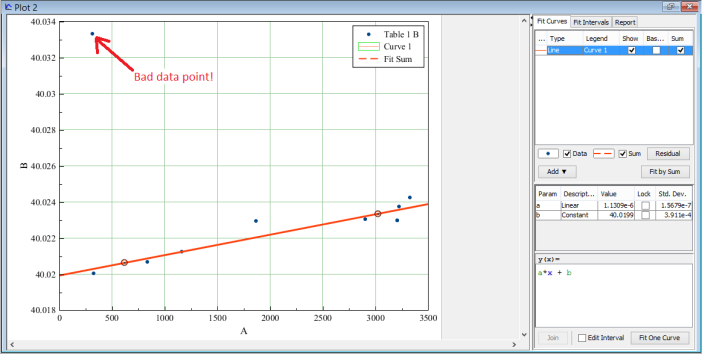

The method involves some simple use of matrices. You begin by representing the transition between the co-ordinates of the pixels of a given location on the map (x and y) and the longitude and latitude (g and t) using a matrix:

Here, a-d are the constants that dictate the stretching and rotation to get from one co-ordinate system to the other, whilst G and T are the latitude and longitude of the x = y = 0 location on the map. The task is to adjust all six of these parameters to the values that produce the smallest error when you plug in the x and y co-ordinates of each of your data points and calculate the longitude and latitude, or vice versa. You could try to adjust all six of these in a single computerized fitting routine to find the best values, but that would require writing your own computer code specific to this particular regression analysis and may well not work anyway. Adjusting six different parameters all at once to try to find the best values would be like wandering around blindfolded trying to find the highest peak in a mountain range, in six-dimensional space; a difficult task for a computer program or a human.

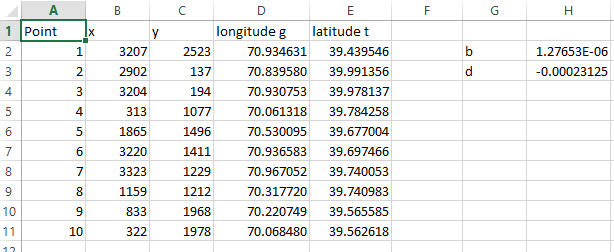

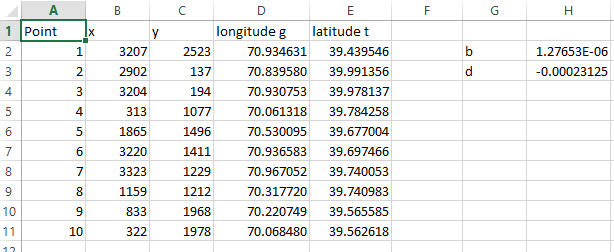

But it is possible to break the problem down into a succession of linear fits, each of which is a simple routine which can be performed on a number of proprietary software packages (I used magicplot). You begin by obtaining approximate values for 2 of the variables in the rotation / stretching matrix (I chose b and d) using the data from 3 of the data points. This is just a matter of solving the simultaneous equations you get when you multiply out the matrix above as applied to each data point, so I shall skip this step. You end up with a set of 10 data points (or as many as you had the patience to type in) and values of b and d calculated using the first 3 data points. Looking something like this:

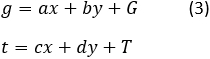

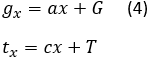

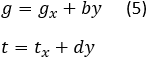

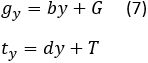

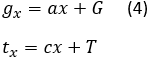

Next, for each (x,y) data point you calculate (gx,tx), the values of (g,t) for the location (x,0) (rather than (x,y)). This is done using the matrix:

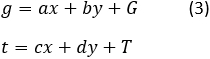

Multiplying out (1) gives separate equations:

As does multiplying out (2):

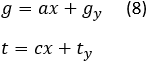

Substituting (4) into (3) gives us:

Using the values of b and d from the initial calibration, we can use (5) to calculate gx and tx for every data point. So now we have all our data points in the form:

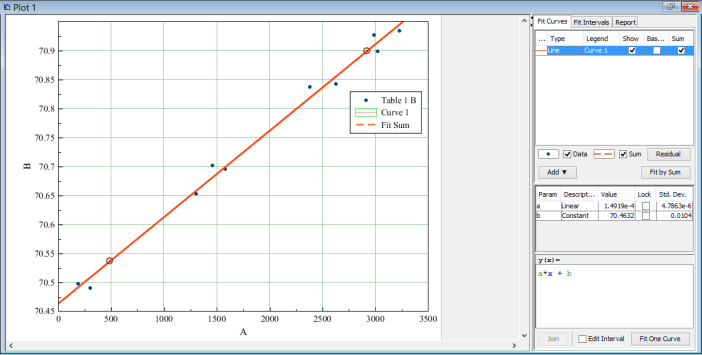

If we plot graphs of gx and tx as a function of x, where each data point is a dot on the graph, they should be reasonably straight lines, described by equation (4) and straight lines can be fitted to them using proprietary software as discussed earlier – this is where the computer does the really hard work for you. What the computer does is try out lots of different values of a, c, G and T and find the values which result in a straight line passing as close as possible to all the data points. This is the regression analysis that I mentioned earlier and is the key part of this whole procedure. This is what allows you to make use of all 10 data points, and weed out the bad ones, rather than just using 3 data points and being a bit stuffed if one of them turns out to be bad. We can feed in as many data points as we need to, to compensate for the fact that the surveying on google earth is not as accurate as we would like (as discussed earlier).

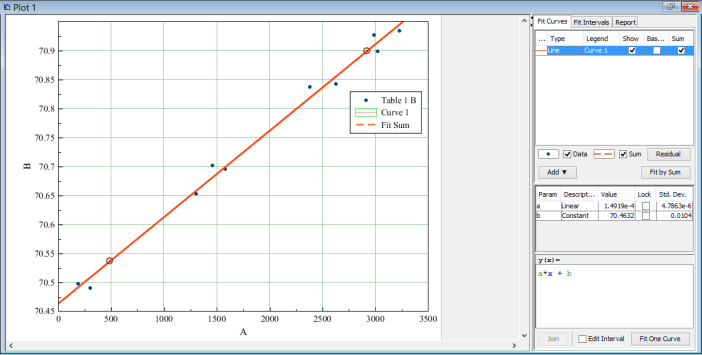

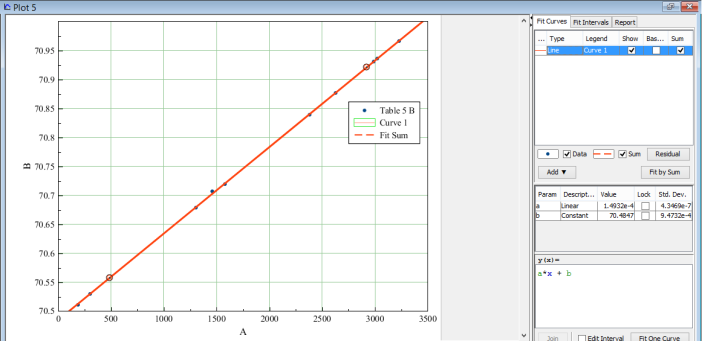

Above is an example of the graph which the computer fits the line to, it has fitted the line and found values for the variables a and G (the variable the computer calls b is actually G). As you can see, the data points are rather spread out around the fit. This is because we have used values of b and d which are not that accurate. Performing the same procedure with the graph of tx as a function of x gives values for c and T.

So what we need to do now is use the values of a and C we have just calculated to do more regression analysis to improve our initial guesses at b and d. To get the set of data points in a suitable form for this we set x = 0, i.e. the following matrix:

Multiplying out this matrix gives:

Substituting (7) into (3) gives:

Using equation (8) and the values of a and c we have just calculated we can, for each data point calculate (gy,ty), the values of (g,t) for the location (0,y). So we now have all our data points in the form:

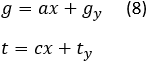

We now plot gy and ty as a function of y. These should also be straight lines (described by equation (7)) and performing the regression analysis gives us more accurate values for b, d, G and T. We now repeat the first 2 regression analyses with our more accurate values for b, d, G and T. The second run of the regression analysis I showed in the picture above looked like this:

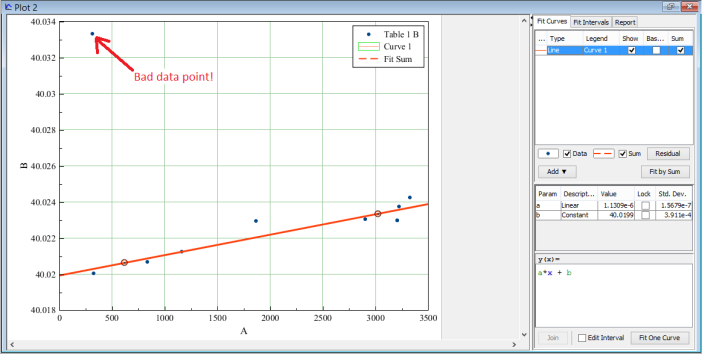

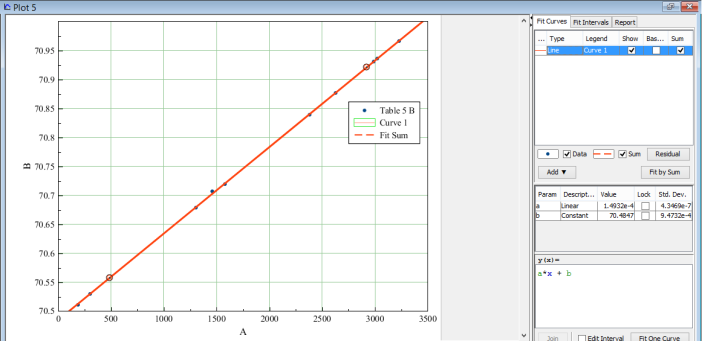

As you can see, the (x,0) data points this time round are lying much closer to the line of best fit. This is because they have been calculated using the more accurate values of b and d. The first time round, the computer gave a = 1.4919 x 10-4. This time it is saying a = 1.4932 x 10-4. To complete the fitting process, i.e. get the most accurate values you can for a, b, c, d, G and T you just repeat the regression analysis in the order described until each analysis gives you the same values as the previous round of regression analysis. When this is the case you have achieved convergence. I performed this procedure for several maps covering this area of Kyrgyzstan and needed to do 2 or 3 rounds of regression analysis to achieve convergence – it will take more rounds if one of the data points you used to get the initial values for b and d was a bad one. There will always be the occasional bad data point – perhaps it was set at a road junction which has been moved since the Soviet map was surveyed, or involves a summit which google earth doesn’t quite have the resolution to get right. The regression analysis allows you to spot and remove these bad data points – while most data points will lie close to the line of best fit, the bad data point will lie some distance from it. You can spot this (see example below), delete that data point and rerun the regression analysis without it.

Regression analysis with bad data point

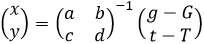

So…we now have accurate values for a, b, c, d, G and T which allow us to take any point on the electronic copy of the Soviet map and, using the pixel co-ordinates (x,y) calculate the latitude and longitude (g,t). It is sensible at this point to run all our original data points through equation (1) and see how close our calculated latitude and longitude are to what google earth says. It is also possible to rearrange equation (1) taking the inverse of the a,b,c,d stretching / rotation matrix to get an expression which gives us the pixel co-ordinates (x,y) on the map when we feed in the latitude and longitude (g,t):

Anyway, now we get to the whole point of this exercise, the ability to plot the lines of constant latitude (going roughly but not exactly across the map) and constant longitude (going roughly but not exactly up and down the map). Each latitude line corresponds to a specific constant value of t. It starts at a specific value of x (which we decide) near the left-hand side of the map, and finishes at another specific value of x near the right-hand side of the map. Rearranging equation (3) gives us the value of y which corresponds to each value of x, when we enter t and the other parameters (which we now have accurate values for):

We can also obtain an equation to do the same things for the lines of constant longitude:

Drawing all these lines on the maps takes a while and Phil did most of this… To finish, here is the section of map shown earlier, with the WGS84 latitude and longitude lines marked on it:

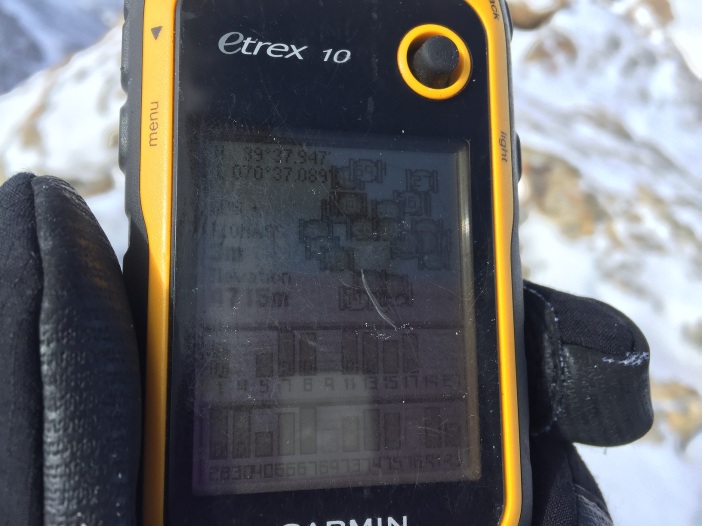

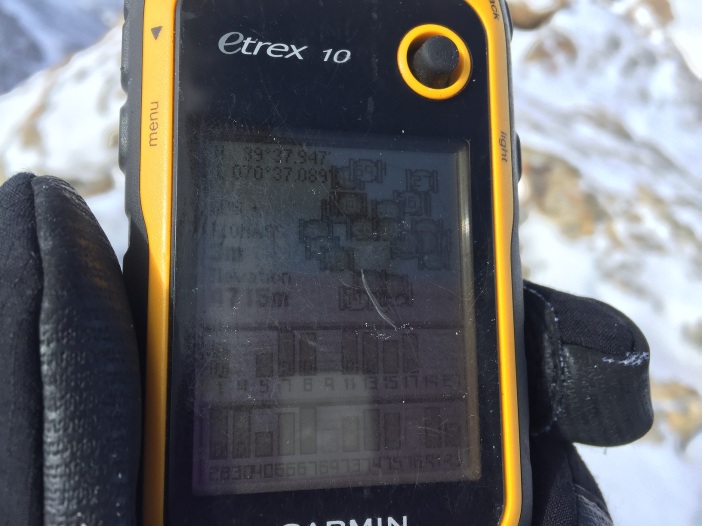

Note that, in the mathematical procedure outlined above, there is nothing to force the latitude and longitude lines to be perpendicular to each other. They just come out perpendicular to each other anyway, because the procedure is getting them exactly where they should be! So now, you can read the WGS84 datum latitude and longitude off your GPS (top left corner in the photo below) and locate yourself on the map:

My Garmin etrex 10 GPS, obtained second hand from my good friend and climbing partner Michael Finegan, has seen better days after going on 4 expeditions. It is getting hard to read the screen (photo copyright (c) Ciaran Mullan).

John Proctor

PS I should perhaps mention why it is that I enjoy matrices and regression analysis; in my other life I am a physicist.